The Anatomical Chart of Clutter

Book Cover of the Chinese edition of The Anatomical Chart of Clutter

The Anatomical Chart of Clutter was originally published in Japan in 2013, written by architect Nobuhiro Suzuki and was introduced to Chinese audience in 2014. That is to say, I bought this book nearly 10 years ago. Having moved from place to place, this book is still with me because it holds tremendous personal importance to me! Undoubtedly, this is the first book I want to write about in the first edition of our book design review!

First thing first:

What’s so special about this book?

The answer is its illustration.

It’s rare to see a paperback in the US using cartoonish illustrations as its main content. Most of the interior design books here are filled with glamorous photos that make you think you are either too poor or too messy… 😂 but this book is filled with practical advices, and it’s very economical to produce!

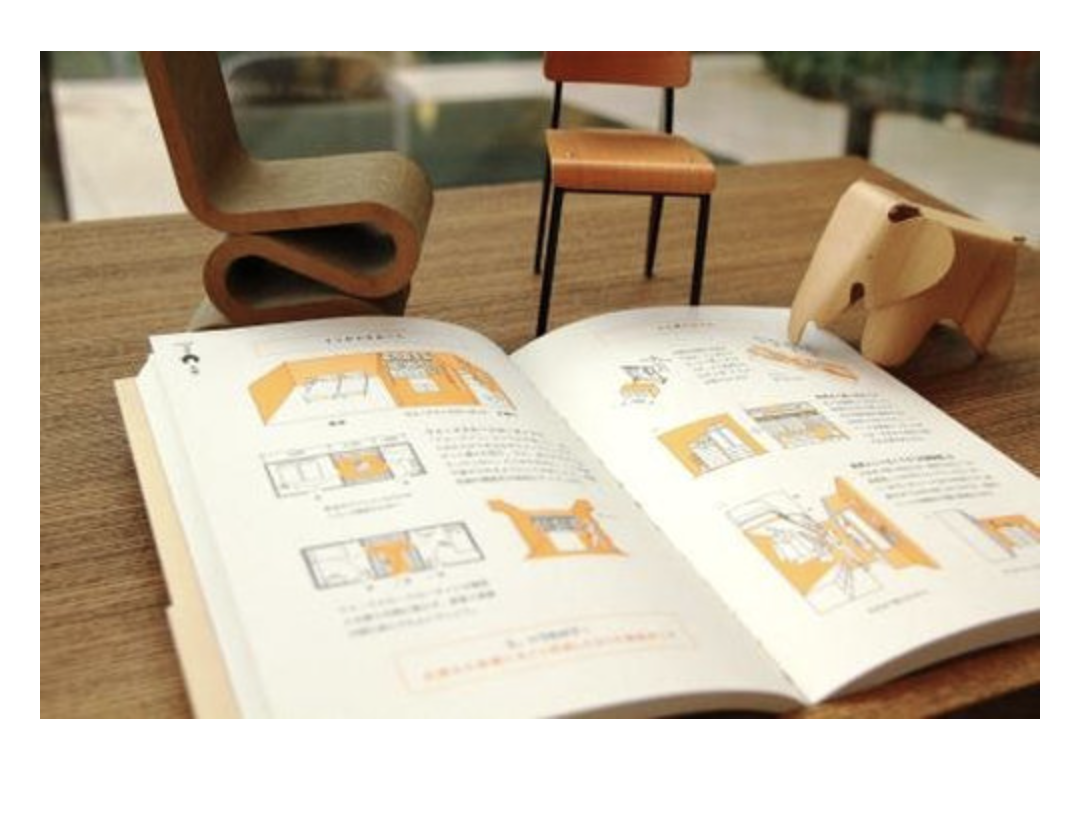

Let’s look at its pages for example:

Translation of the section title: The Hierarchy in the Cloth Society

This page teaches its reader how to organize all the cleaning supplies in the kitchen. In author Nobuhiro Suzuki’s words:

The shiny photos you saw in those interior design magazines hid a little lie. Just compare those photos to your own kitchen! The most common things in the kitchen all disappeared! Tea towel, hand towel, table towel… no one was invited to the photo shoot!

However, these towels erased from design magazines are the most hardworking guys. And they are always wet. That’s why we need to find them a bright and dry corner to hang.

Now look at the images on “The Hierarchy of the Cloth Society” page. From top to bottom: clean ones to dirty ones; dry ones to wet ones.

“That’s how you should arrange your towel hangers in your kitchen,” says Mr. Suzuki.

The book is filled with practical wisdom like this, and the cartoonish illustrations perfectly fit the message the book is trying to convey: practical everyday tips on homemaking.

Wisdom in the Playful Design Details

Starting with the dust jacket of the book, it’s been enticing the reader to keep an curious eye on our living space.

Text on the dust jacket: Which of these kitchen cabinet combinations is the most efficient design? Turn to page 24 to find out!

Throughout the book, the architect’s careful design consideration was conveyed in the humorous cartoons that explains the user scenario, and in the easy diagrams for laypeople.

In the above example, Mr. Suzuki suggested that kitchen counter should reserve enough space on both sides of the sink and that of the stove. This way, you’d have a streamline workflow as you prepare your dishes.

Similarly, Mr. Suzuki discussed the floor plan for a walk-through closet, which would make the dressing routine more smooth.

Same philosophy, he argued that small sofa chairs might be a much better choice than a large couch. We might have imagined to have a big couch so that the entire family could sit together, but in reality, most of the time the big couch was taken by our dog or piles of laundry. Small sofa chairs are modular thus much more flexible.

In his writing Mr. Suzuki laughed at himself for making practical recommendation to his clients, but his clients oftentimes ended up buy shiny, expensive, and impractical design.

What are you gonna do?

This is something I particularly like about this book. Clients don’t always listen to the most practical advice - Advertising professionals are proud to be able to sell people products they don’t really need. When people just bought their new house, they want to keep their dream going - with Instagram-ready interior design - instead of coming down to the ground.

Therefore we need a book - a book for people who don’t seek solution in buying stuff, but in understanding and applying the underlying principles.

The Unsung Hero Is The Illustrator

The Chinese edition only credited the original author, the translator, the editors, and the book designer. I had thought that Mr. Suzuki drew all the illustrations.

But no.

In the Acknowledgement of the book, Suzuki thanked Mr. 鸭田猛 for turning his messy sketches into such delicate illustrations. I couldn’t find this person by Googling the Chinese translation of his name. It’s a rare name, and I’m afraid it’s a pen name anyway. From what I could gather in Japanese online bookstores, there was no attribution to the illustrator either.

Is the illustrator a full-time employee of the publisher, therefore not worth mentioning?

In the U.S. or Europe, illustrators are usually freelancers. They maintain a distinctive drawing style, and the art directors would call different illustrators to fulfill different projects.

When I see an illustration I like, I will go check out the artist’s website and see what other projects they’ve done. What a pity that I couldn’t pay respect to this book’s illustrator!

Languages & Localization

The home design ideas discussed in the book are centered around Japanese lifestyle. That might have been why this book was unfortunately not introduced to English readers.

Traditional Chinese (Left) Japanese (Right)

I found its Traditional Chinese edition on books.com.tw, and original Japanese edition on Amazon Japan.

From the book cover design, we can see that the Traditional Chinese edition followed more closely to the original Japanese edition. Even the translation of the title was closer to its original meaning

The literal translation of the Japanese title, not the English text you see on the cover, is:

The Anatomic Chart of Decluttering - The Structure That Creates Comfy Residence

The literal translation of the Traditional Chinese title:

The Anatomic Chart of Residential Organization - Tips on Creating a Comfortable Living Environment

The literal translation of the Simplified Chinese tile:

The Anatomic Chart of Residential Layout - The Key to Home Renovation Is to Design A Good Floor Plan!

Japan and Taiwan share similar lifestyles. The tips given in the book could be more relevant. For instance, the book discussed many design cases for single family houses. This uncommon in China, and I’d guess that’s why the Simplified Chinese edition emphasized “floor plan” and “renovation”, instead of “structural design” implied in the Japanese text.

Traditional Chinese (above) Simplified Chinese (below)

Also, Simplified Chinese books all read from left to right, same as the English books. However, Japanese and Traditional Chinese books might mix vertical and horizontal layouts, but the pages turn from right to left regardless.

In the example above, we can compare the layout design of the same content in Traditional and Simplified Chinese. In the Traditional Chinese book, the chapter blurb was on the right hand side, and the text is organized vertically. Its opposite page reads from left to right, horizontally. The Simplified Chinese book has the chapter blurb on the left hand side, and the entire spread reads from left to right.

I can’t find any page example of the Japanese edition, except this blurry one from Asahi News:

Comparing this page to the book I have at hand, I’d guess the Japanese book uses the same layout as Traditional Chinese book.

Whether the text reads from left to right or from top to bottom may seem to be a negligible detail, just a difference in reading habit. However, the difference becomes prominent when these two formats of text have to work within the same book.

Penguin Books has been publishing a bilingual book series for language learners, called The Penguin Parallel Text. The books consist of short stories in a foreign language, with their English translations laid next to the original text, hence the name “parallel text”. Started in 1960s, they produced books in Russian-English, German-English, Italian-English, French-English, and Spanish-English, but the Japanese-English book did not come to fruition until 2011. The Eurocentrism was one of the reasons, but more importantly, it seems, that the barrier lies in the reading habit.

New Penguin Parallel Text: Short Stories in Japanese

The editor of Short Stories in Japanese, Michael Emmerich wrote:

On one page, the Japanese text streams down in vertical columns like the rain, progressing one line at a time from right to left, just as in a Japanese book; on the other, horizontal English text gushes across the paper to meet the Japanese in the gutter. For the first time in the history of these volumes, two languages have overcome the stand-offish, never-the-twain-shall-meet dictates of parallelism, and have discovered a means of coming together. It’s stunning. It’s exhilarating!

I had not realized how significant this was until Mr. Emmerich put it this way. Not only that the book designer needed to manage both the horizontal layout and the vertical layout in the same book, but also they would need to match the length of the translated text and the original text, so that they remain in the same spread of the pages!

Final Thoughts

The “picture book (図鑑/图鉴/圖鑑)” is a popular book format in Japan. Unlike the picture books in the US, which is often considered as children’s book, the 図鑑 format is commonly used to publish explanatory subjects in popular science, such as architecture design, botany, animals, history… and so on. It has its heritage from Japan’s manga tradition.

The U.S. audience seems to prefer more sophisticated rendering of the imagery, and we don’t see many 図鑑 type of books. (Cartoon books unmistakably belong to the Humor section in bookstores here!)

I hope one day this will change. After all, it’s much more cost effective and straightforward to produce 図鑑 than full-color high-res photography books, and bringing down the cost means knowledge gets to spread faster and farther!